GoT: feminist or misogynistic series?

Fig. 1 and 2: Daenerys Targaryen

chance of death:

17%, Andals' queen and Ros

chance of death:

93%, brothel's queen - ©HBO

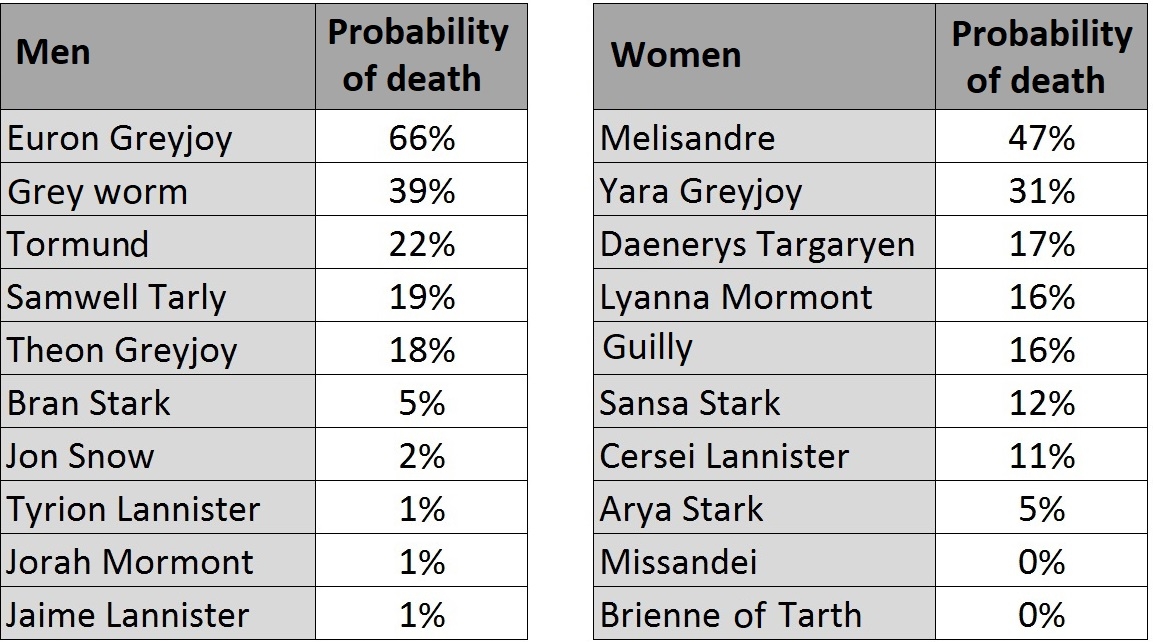

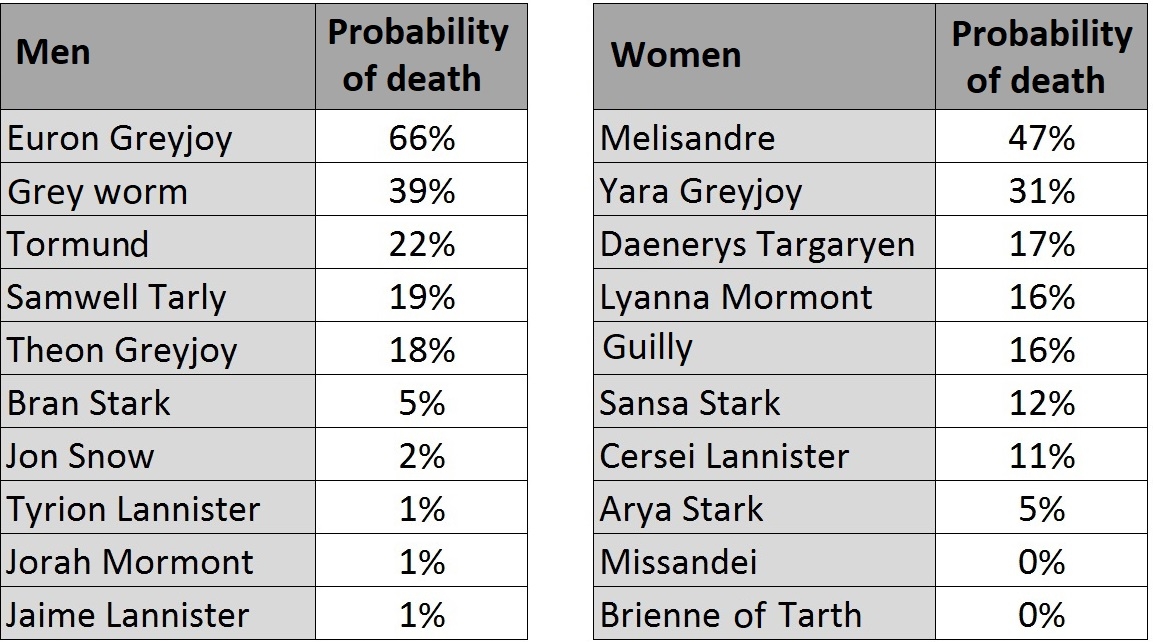

According to its detractors (are there ?), the series was created by men and for men. It supposedly minimizes the severity of violence perpetuated against women, and portray rape as commonplace. Granted, it needs to be noted that Daenerys Targaryen, Sansa Stark chance of death: 12% and Cersei Lannister  chance of death: 11% (the three female characters that appear the most of screen) are all victims of marital rape. The message isn’t pretty. The floor is to the advocates... |

According to its advocates, the series dares to show strong and unshackled female characters. Even though medieval fantasy doesn’t lend itself to it ! Can you imagine Daenerys during the medieval ages ? A hard task... Arya Stark chance of death: 5% breaks the established codes by learning how to fight in spite of her status. Brienne  chance of death: 0% is the sole character who is loyal, just, strong and female simultaneously. Why would Tormund Giantsbane  chance of death: 22% fall victim to her charm otherwise? |

According to its detractors (are there ?), the series was created by men and for men. It supposedly minimizes the severity of violence perpetuated against women, and portray rape as commonplace. Granted, it needs to be noted that Daenerys Targaryen, Sansa Stark

chance of death:

12% and Cersei Lannister

chance of death:

11% (the three female characters that appear the most of screen) are all victims of marital rape. The message isn’t pretty. The floor is to the advocates...

According to its advocates, the series dares to show strong and unshackled female characters. Even though medieval fantasy doesn’t lend itself to it ! Can you imagine Daenerys during the medieval ages ? A hard task... Arya Stark

chance of death:

5% breaks the established codes by learning how to fight in spite of her status. Brienne

chance of death:

0% is the sole character who is loyal, just, strong and female simultaneously. Why would Tormund Giantsbane

chance of death:

22% fall victim to her charm otherwise?

Fig. 3: In the top six "most appeared characters", 4 of them are female

Fig. 3: In the top six "most appeared characters", 4 of them are female

In the top ten "most appeared characters", 4 of them are female, so we can consider this as an almost parity! In the top six, here come the girls powa. This is to consider regarding the fact that female characters have a higher mean appearance time screen, and a higher popularity than male ones. Moreover, some females are experiencing a meteoric social rise (Fig. 3). This is particularly true for Dany, who went from terrorized little girl to powerful queen, joined by many mighty people including the Starks. This social rise is even more impressive considering the very patriarchal society where it took place.

Okay, some of the female protagonist are fighting to get rid of it, but can we really study only few Secretary of State women then say that a country is not sexist anymore?

Fig. 3: The subjugation of female characters

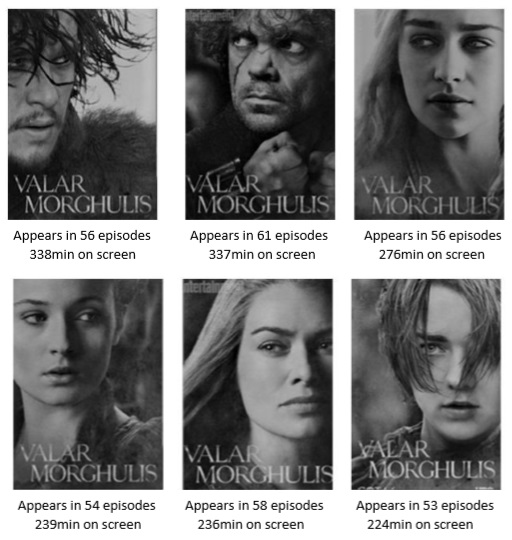

The writers showcase a type of Middle Ages that is fantasized about and unfamiliar. The world of Game of Thrones appears thus as a masculine one (there are three times more male characters than female!).

During the medieval ages, "it’s inappropriate for a woman to fight or lead" [SourceJ. de Cessoles, (XIVème s.) "Jeu des échecs moralisés".]. In the show, just 17% of female characters are seen in combat (against 77% of male characters). One out of four female characters has a political role (against one out of three for male characters).

Furthermore, even when they reach a political status, it’s limited. 28% of the "female politicians" of the series turn that way through marriage (in season 1, Cersei is only a consort). This isn’t the case for any male character.

Female characters also hold a lesser social rank (Fig. 3). The argument of objectification can be made, as one out of four female characters is subjected (peasants, servants, prostitutes working for or kept by a tenant, slaves). It’s the case for only 2% of male characters.

We come across this objectification with the relation to the body. 26% of actresses appear naked at least once (with only 11% of actors, but Jon Snow

chance of death:

2%’s ass compensates, right?) Women are also almost the exclusive victims of sexual violence (granted… there’s also Theon Greyjoy

chance of death:

18%). The tale of Cersei’s rape by Robert Baratheon

chance of death:

99% shatters the myth of Westeros’s liberator. Morality falls at an all-time low when Jaime Lannister

chance of death:

1% rapes his sister in a place of worship and over the corpse of their son. Daenerys’s rape during her wedding night reveals her brother’s betrayal by selling her to a barbarian (Drogo

chance of death:

98% would then attempt to redeem himself). Sansa’s rape by Ramsay Bolton

chance of death:

96% is an act of war against the Starks.

Numerous fans are arguing about the sexism aspect in the Game of Thrones series. The most frequent argument point that the story takes place in a medieval context. This is therefore supposed to be the reality of the so-called "Middle Age". Nevertheless, dragons and White Walker do not bother anyone... This "historically accurate scenario" argument should perhaps be put in perspective...

However, does objectification prevent death?

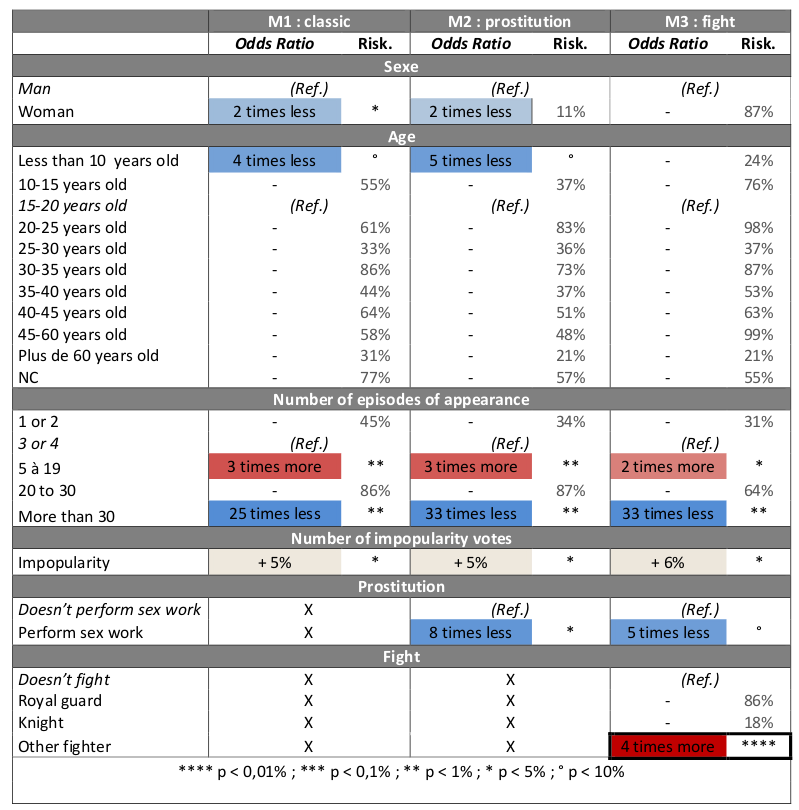

That’s what we could think. 38% of the female characters die during the course of the show, against 56% of the male characters. However, caution is necessary… Female and male characters differ in many ways. It becomes a problem for measuring the chances of dying. It’s necessary to determine if female characters don’t die as much because they are women (natural effect of gender on mortality), or if it’s their special trait that protects them (composition effect; for example, if the prostitutes die less, and female characters prostitute themselves more frequently, so female characters are protected by this composition effect). To neutralize these composition effects, we resort to regressions. (Fig. 4).

Reading (model 3, combattant.e): All things equal otherwise (gender, age, appearing episodes, unpopularity, prostitution), fighting characters (excluding royal guards and knights) die more frequently than non-fighters. The risk to take to confirm this is less than 0.01% (****)! Compared to a non-fighter, an « another fighter » has four times more risk of dying.

Fig. 4: Equality between men and women… for mortality

First model: The first model confirms that, with equal age, appearing episode, and unpopularity, female characters have a lower chance of dying (with a low risk of being wrong: 1.5%): compared to male characters, female characters are twice as unlikely to die.

Second model: We know that female characters are more often prostitutes than male characters. As it turns out, this status prevents death (10% of prostitutes die. Ros’s death is impactful, but is an exception). So we add the trait of prostitution in the model. In that manner, we assume male and female characters prostitute themselves as much as the other. The risk to take to affirm that female characters die less increases (from 1.5% to 10.5%). Therewith, the act of prostitution prevents death significantly more than being a female character.

Third model: However, we also know that male characters fight much more often. And, as it stands, fighters are more exposed to death (70% of them die). So we add the trait of combat in the model. That way, not only do we assume male and female characters prostitute as much, but also fight as much. From here on out, we cannot say there’s a difference in mortality between male and female characters anymore.

To sum up, if male and female characters prostituted themselves and battled as much, they would, in turn, die as much as the other. Feminists can be reassured: gender equality exists in Game of Thrones... when it comes to death, at least.

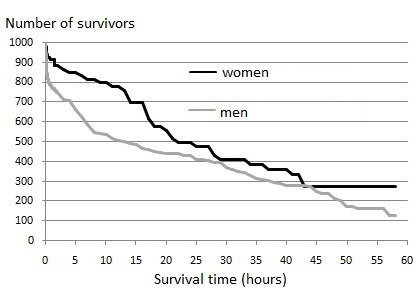

At this stage, we know that female characters die less than male characters throughout the series (meaning, during the first 7 seasons). However, we know that this difference can be explained by the protecting traits of female characters, who fight less and prostitute themselves more. Despite this information, we know nothing about the mortality’s frequency.

Fig. 5: Moments of extreme mortality at different times

Fig. 5: Moments of extreme mortality at different times

Female and male characters don’t die with the same frequency (Fig. 5). Male characters are faced with death right from their first minutes of "life" in the series: 22% of them die during the first hour on screen, against 9% for their female counterparts. A female character can hope to live for 29 hours, while male characters for 22 hours. Once again, this can be explained thanks to composition effects. Striked down as fast as they appear: that is the fate awaiting a large portion of fighters (predominantly male characters).

Furthermore, the writers only have about a hundred female characters at their disposal. Better not kill them all immediately; otherwise women would be an endangered species at Westeros!

Not all in sunshines and rainbow for female characters that stay alive, though, who, later on (between the 15th and 25th survival hour), are faced with a very high mortality. As such, after 15 hours of survival, a male character can hope to live for another 4 more hours than a female character.

Fig. 6: Some probabilities of dying

Fig. 6: Some probabilities of dying

Finally, we would like to present our "optimal" model’s results. It explains as best as possible the mortality, while keeping just the most influential traits to the risk of dying (for example, the number of appearances, being a fighter or not, their nobility rank). This model then allows us to assess the characters’ risks of dying during the final season (Fig. 6).

These risks are retrospective. They are based on the characters’ past traits to establish their risk of dying during the first 7 seasons.

Will these past trends be followed in the final season? Will the writers foil all of our predictions? We don’t know about you, but we can’t wait to answer this question… in 2019!

Barbero, M. (2016) « Les différents statuts de la femme au Moyen Âge ». In: La compagnie littéraire. [Online]: http://www.compagnie-litteraire.com/statuts-femme-moyen-age/

Brossat, T. et Delavier, L. (2014). « “Game of Thrones”: violence, sexe et Moyen Âge ». In: Esprit, n°8, p. 240. [Online]: https://www.cairn-int.info/article-E_ESPRI_1408_0217--game-of-thrones-violence-and-sex-in.htm,

Cesbron, M. (2016). « Pourquoi Game of Thrones est un cas clinique ». In: Le Point Pop. [Online]: http://www.lepoint.fr/pop-culture/series/pourquoi-game-of-thrones-est-un-cas-clinique-17-05-2016-2039830_2957.php

Crastor, H. (2014). « “Game of Thrones”. La périlleuse condition féminine à Westeros ». In: Courrier International. [Online]: https://www.courrierinternational.com/article/2014/04/04/la-perilleuse-condition-feminine-a-westeros

Delporte, C. (2017). « ”Game of Thrones”: pourquoi ça fonctionne encore ? ». In: Les Echoc. [Online]: https://www.lesechos.fr/13/07/2017/LesEchosWeekEnd/00085-013-ECWE_-game-of-thrones---pourquoi-ca-fonctionne-encore.htm

François, M. (2019) « Game of Thrones: Une série féministe, vraiment ? ». In: NEON. [Online]: https://www.neonmag.fr/game-of-thrones-une-serie-feministe-vraiment-524450.html

Jones, R. (2012). « À Game of Genders: Comparing Depictions of Empowered Women between À “Game of Thrones” Novel and Television Series ». In: Journal of Student Research, Volume 1, Issue 3: pp. 14-21

Héas, S., Bodin, D., Robène, L., Meunier, D. & Blumrodt, J. (2006) « Sports et publicités imprimées dans les magazines en France: une communication masculine dominante et stéréotypée ? ». In: Études de communication, 29(1), 131-156. [Online]: https://www.cairn.info/revue-etudes-de-communication-2006-1-page-131.htm.

Langlais, P. (2017). « “Game of Thrones”, le succès en dix leçons ». In: Télérama. [Online]: http://www.telerama.fr/series-tv/game-of-thrones-le-succes-en-dix-lecons,160044.php

Lyon, C. (2015). « Game of Thrones. Pour en finir avec la femme objet ». In Courrier International. [Online]: https://www.courrierinternational.com/article/game-thrones-pour-en-finir-avec-la-femme-objet